Opinion: American bourbon trail delivers nasty spills, investor thrills.

Each of the 6,000 hand-numbered bottles of Indiana bourbon whiskey named after Greg Metze sells for about $75.

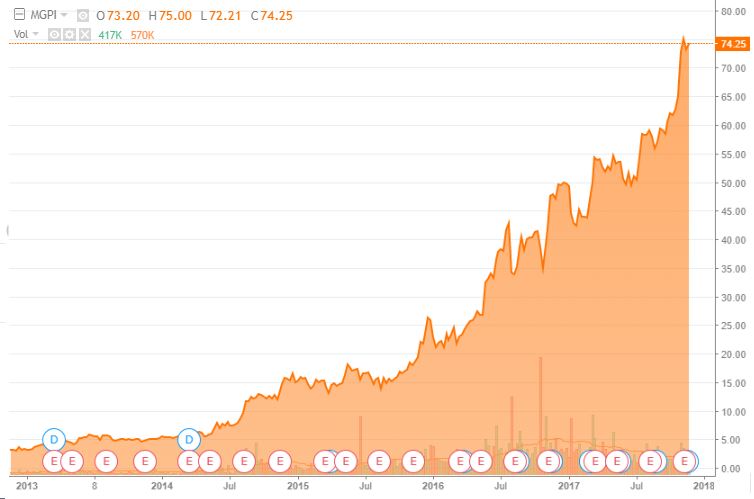

But if you really want to experience the liftoff in American craft-whiskey production, you’d have done well to invest in his employer, MGP Ingredients MGPI, +1.67% , whose shares climbed 64% last year.

Brown spirits are booming, and so are craft distillers.

It is a cautionary tale. Big spirits companies are crowding the U.S. market with their own brands, and niche marketing strategies. And behind every market boom, a bust inevitably lurks. The number of craft distillers has increased more than tenfold in a decade, and the average firm is only three years old, according to research by Eamonn Ferry, Francois Mosnier and Jean Letzelter of Exane BNP Paribas.

But for now, American whiskeys are at least as fun to watch as to savor.

The MGP story is just one example. In danger of being left behind amid a generational boom that is reshaping U.S. grain fields and export markets, the founding family confronted management during a proxy contest for control of the Atchison, Kansas-based company in 2013. Lurching from quarter to quarter, MGP was trading for about $6 a share, less than one-quarter its market value today.

The grandchildren of founder Cloud Cray Sr. seized operational control. And in July 2014 they installed former Brown Forman and Next Level Spirits executive Gus Griffin as CEO.

“I expected to find a bruised and battered company after that proxy fight,” Griffin told me. “What I found was a positive, collaborative culture, unlike any I’ve experienced. … It was very clear they had underutilized assets. They had tremendous macro trends that were going to benefit them.”

With 300 employees and two distilleries in Atchison and Lawrenceburg, Ind., MGP’s primary business is supplying distilled alcohol and ingredients to other makers, who apply their own labels—and finishing touches—to the product. So while MGP is not a craft distiller, it supplies big and small producers alike with the fixings, including a dozen or more recipes that can be custom-blended and finished. In 2014, MGP generated $257 million in sales on 18.5 million cases of whiskey, 500,000 cases of rye, and 6.3 million cases of gin. It also produces specialty wheat-based proteins and starches.

The term “craft distiller” defies formal legal definition, as I’m going to discuss in a moment. But the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States categorizes small distillers as those that sell fewer than 100,000 cases a year. And the American Distilling Institute, which claims to speak for the very small maker, puts the upward bound on craft production at 42,060 cases; and limits to 25% the total investment that non-craft alcohol beverage companies can have in these independent distillers.

So what is the sincerest form of flattery? That’s right, imitation.

Jim Beam appropriated the language of the craft distiller in affixing “handcrafted” to the labels of the world’s best-selling bourbon, according to a civil lawsuit filed last February in federal court in Los Angeles. In what might well have worked as a late-night TV parody, the complaint trotted out factory floor diagrams and photographs of industrial machinery, all the while faithfully parroting the Jim Beam claim that “creating the world’s #1 bourbon requires skilled craftsmen and a whole lot of patience.”

Plaintiff’s attorney Abbas Kazerounian quoted the Merriam-Webster dictionary as defining “handcrafted” as being “created by a hand process rather than by a machine.”

Unintentionally or otherwise, some of the lawsuit’s language is bitingly satirical, all the while drawing attention to the “offending label,” which Kazerounian describes as “immoral, unethical, oppressive, and unscrupulous,” and a “continuing threat to consumers.”

“Consumers have purchased Jim Beam Bourbon under the false impression that the bourbon was of superior quality by virtue of being ‘handcrafted,’” Kazerounian argued, adding that the consumers overpaid.

Judge Larry Alan Burns disagreed. “Although misdescriptions of specific or absolute characteristics of a product are actionable,” the judge wrote, “generalized, vague, and unspecified assertions constitute mere puffery upon which a reasonable consumer could not rely.”

He dismissed the case in August.

Other lawsuits took offense at such terms as the Miller Coors claim that its Blue Moon beer is “artfully crafted,” and that Tito’s Handmade Vodka is “handmade.” These actions also failed. U.S. Judge Robert Hinkle, having thrown out a similar complaint related to the Maker’s Mark brand of bourbon in May, dismissed much of the Tito’s lawsuit in September, writing, “One can knit a sweater by hand, but one cannot make vodka by hand. Or at least, one cannot make vodka by hand at the volume required for a nationally marketed brand like Tito’s. No reasonable consumer could believe otherwise.”

Words do matter, of course. Otherwise the former Beam Inc., based in Deerfield, Illinois, wouldn’t have borrowed the language of the craft distiller to market its mass-produced bourbons. And its new owner, Osaka, Japan-based Suntory Holdings Ltd. 2587, +0.51% , which announced a $16 billion offer to buy the American company only a month before the Jim Beam suit surfaced, wouldn’t have defended it.

In the three-plus years Beam operated as a standalone company (after being spun off by Fortune Brands in 2011), it boosted expenditures on advertising and marketing by 30% to get consumers to spend more—and pay more—for its products, which also include Skinnygirl and Sauza Tequila. In turn, its operating income rose by 35% to $617.1 million, on an 18% increase in sales to $3.1 billion.

“Mere puffery,” to quote the judge, became worth quite a lot. Meanwhile, only months before its sale to Suntory, Beam said it discovered in late 2013 that it was overstating millions of dollars in sales and profits by recording some revenues too soon. Despite the restatement, the final merger agreement with Suntory identified $108 million in stock benefits for Beam’s board and executives.

In reviewing six years of financial filings by Beam and its predecessor, Fortune Brands, I found little reference by management to such terms as quality or taste that might support the trend toward higher sales and profits. Instead, I found phraseology like “we will upweight marketing investment in the second half behind our most exciting brands and innovations,” as in an 8K filing by the company in August 2012. And Beam’s annual report to shareholders that same year promoted a TV advertisement with Jimmy Fallon promoting its Maker’s Mark brand: “It is what it isn’t,” the copy writer attested.

Darek Bell, the owner of Corsair Distillery in Nashville, whose craft whiskeys, ryes and gins have amassed dozens of awards for quality and innovation, says, “Craft spirits are very simple. Craft means small, independent, and actually made by that distillery.”

“I think the heart of the matter is the big guys are mad that they cannot just keep making the same old stuff, and that they have to change due to evolving consumer tastes.”

“Their approach,” Bell says, “seems to be to confuse the consumer by both discrediting the word craft and simultaneously by saying they themselves are craft.”

MGP has taken a lower profile in riding the boom along the U.S. bourbon trail. Its chief grain buyer is a local farmer on the Great Plains who sells some of his own crop to the company.

Last fall, MGP custom-blended three house bourbons to roll out its first branded product, bearing master distiller Greg Metze’s name. New York whiskey connoisseur Tony Sachs says it is “a tremendous display of just how good MGP is at both distilling and aging.”

But the real testament is the stock price.

CEO Griffin pointed out the company in January 2015 forecast that it will quadruple adjusted operating income in five years. That figure of $8.5 million for all of 2014 nearly tripled to $22 million through the first three quarters of 2015, the company announced in November.

“We’ve gotten a lot better traction than we ever thought,” Griffin says.

And about the shift in consumer tastes in distilled spirits from clear vodkas to American heartland brown bourbons, Griffin says, “We can debate whether this is going to be a 15- or 25-year run. But I don’t think there’s any question of whether it’s going to be a three- or five-year run.”

“It’s a long-term shift in preference in consumer tastes.”

Read more from Elliot Smith.